- Home

- Anna Sweeney

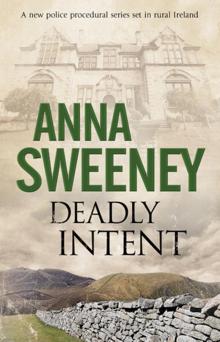

Deadly Intent Page 2

Deadly Intent Read online

Page 2

But Nessa still wished she had paid more attention to Maureen, who had been hanging around the house that morning, moody and unsure of how to spend the day. Nessa was very busy, and she was also feeling the end-of-season weariness that September brought. So she had been relieved when Maureen finally reappeared from her room dressed to the nines and happy to accept Nessa’s offer of a lift to the local village of Derryowen, half a mile down the hill. Nessa told her to text if she wanted a lift back later, but was quite glad to hear nothing more from her all day.

When Maureen had not turned up for dinner, two other guests reported seeing her at the Derryowen Hotel earlier, while they were drinking mid-morning coffee on the sea-facing terrace. Maureen had greeted them but went indoors, and soon afterwards, they saw Oscar arrive. Through a window, they noticed the pair having a conversation, but then Oscar left on his own. Maureen was still in the hotel bar a while later when the other two guests went off walking, so it was anybody’s guess whether she and Oscar had agreed a rendezvous in the countryside. The whole thing was based on supposition – but if the very worst had happened and Oscar assaulted Maureen on the boreen, it was difficult to see how Nessa or anyone else could have prevented it.

As adults, all of the guests were responsible for their own safety, and in any case, they had been strongly advised not to go walking alone in unfamiliar places. So Dominic’s accusation of negligence was way off the mark. But it was not the legalities that concerned Nessa so much as a feeling that if the week turned out badly, she and her husband Patrick had failed in their job to keep their guests as safe and as happy as possible.

She watched as the lone cloud drifted out of sight. A multitude of questions still weighed her down. How bad were Maureen’s injuries? How soon could she give her own explanations to the gardai? Had Oscar been involved in the incident?

Nessa decided to allow herself five more minutes outdoors. She sat under a big oak tree, on a wooden seat Patrick had given her many years earlier as a present from Malawi. It was made of two pieces of dark wood elegantly fitted together, and as she stretched against its firm support, she reminded herself that at least she was not in a hospital waiting room with Dominic for company – eyes bulging with anger and garish jersey stretched tightly across his belly. She had offered to go to the hospital, of course, but Sergeant Fitzmaurice said that a colleague from Bantry station could call in instead, and pass on any news. But so far, Nessa had had no word from the colleague.

She took out her phone to write a text to Patrick, who had been on her mind all evening. His aunt in Malawi had been ill for several months and he had waited the whole summer for an opportunity to visit her. He had lived in Ireland for over twenty years, and indeed, his father’s mother had been white and Irish, but most of his relatives were in Malawi. He had originally booked flights for the following Sunday – most of the guests would have left by then, and he would have no more guided walks to organise until the October bank holiday weekend.

But he was forced to change his booking at the last minute, because of a threat of strike action at an airport en route. His new flight from Cork airport was at eight o’clock on Thursday evening, three days earlier than planned. He had some business to do on his way to Cork and had left Beara in a hurry that morning. Nessa told herself it was pointless wishing he had delayed until after the weekend – that if only he had been at home, she might have paid more attention to Maureen.

‘I’d rather not leave you holding the fort on your own, Nessa,’ he had said as he pored over internet timetables. ‘We’re both so tired after the summer.’

‘You know I’ll be absolutely fine,’ she had replied. ‘You’ve been hopping with impatience for weeks so please don’t think twice about it.’

She was acutely aware of how important the journey was to him. As an only child whose parents had been involved in political struggle, Patrick’s earlier life had been difficult. His father had died in traumatic circumstances when he was a teenager and his aunt had been his rock of support. He had fretted about her ever since she became ill, and Nessa knew that the sooner he got on a plane the better.

The back garden sloped down to the house, which was called Cnoc Meala, an Irish name that translated as ‘honey hill’ and also ‘sweet hill’. They had picked the name when they heard that a previous owner used to keep bees in a field above the garden. Nessa always felt a surge of pride when she contemplated the house, which they had renovated completely after buying it almost three years earlier.

Moving from Dublin to the far reaches of the southwest coast had been an upheaval for the whole family: swapping her career as a newspaper journalist and Patrick’s as a graphic artist for the uncertain demands of tourism, and parting their two children, Sal and Ronan, from the familiar routines of urban living. For almost two decades, Nessa had loved her work in Dublin, and had made quite an impact with a number of investigative stories; but one morning soon after her mother’s death, she had been struck by an overwhelming feeling that life was too short to spend it all in one place. She and Patrick had occasionally fantasised about living in a scenic and rural community, and while figuring out the move took them some time, Nessa was sure that Cnoc Meala was now their home for life. They had decided to use the same name for their holiday activity business, and in spite of setting it up in the teeth of economic recession, they had survived and paid the bills so far.

It was easy to praise the attractions of the Beara peninsula in their publicity blurb. Splendid mountains and panoramic seascapes, hidden valleys and hedgerows sweet with birdsong were all to be found in abundance between the great bays of Bantry and Kenmare. Even the unreliable weather could be portrayed as part of nature’s colourful drama. The hard part was to convince tourists to base themselves a good distance from airports and major roads. There was also the challenge of group holidays that was not spelt out in any brochure – getting a random assortment of strangers to gel together and enjoy each other’s company for a week.

When things went really well, laughter and chat filled the house until late into the evenings. At other times, Nessa and Patrick settled for a general sense of contentment in the group. But once or twice a year, they found themselves with a few cantankerous guests who could spoil the fun for everyone, and who had to be diverted, humoured and quietly managed all week long.

However, Nessa had had no inkling of trouble ahead when eleven people met for drinks in the living room on the previous Sunday. She had certainly wondered whether Oscar Malden would be difficult to please, because as a well-known entrepreneur and man-about-town, he might find Cnoc Meala rather low-key for his tastes. She had noticed straight off how readily he became the centre of attention. He was not tall or flashy in his appearance, but he had that magnetism that drew others to him and made them feel he was paying special attention to every word they uttered. Of course, he was an old hand at working a room, meeting, greeting and making conversation. Little wonder, really, that Dominic was jealous.

Nessa heard the wind rustling in the oak leaves. It was time to return to the fray. She told herself again that everything would be fine, just as soon as Maureen recovered and Oscar could show that he had played no part in her mishap. Most of the guests seemed to be enjoying their holiday – eight of them in the house, along with a family of three in a self-catering lodge in the grounds – and until tonight’s events, nobody had hinted at a complaint.

Sal called out to her from the back door of the house. Nessa looked back over the text she had jotted to her husband. His plane should have landed at Schiphol airport in Amsterdam by late evening, and he would probably check his mobile before his overnight connection to Johannesburg. She did not want to worry him, however, so she had just said that Maureen had an accident but that everything was under control. In a day or two, she could fill him in on the outcome of police enquiries.

It was clear, in any case, that Dominic was ignorant of one salient fact. Oscar had already left Beara. He had checked out of Cnoc Meala that mornin

g, telling Nessa that an unexpected business problem had come up, forcing him to return to his native County Tipperary. He assured her he was very sorry to leave early, and that he would stay in the area until lunchtime, to take a last walk along the coastal path. His grown-up son, Fergus, who had come down with a minor stomach bug the previous day, would stay on in Beara for the last two days of the holiday.

Nessa reflected that if the gardai required a statement from Oscar, they would have to contact him in Tipperary. And if they learned that he had arrived home while Maureen was still in full health, Dominic’s claims would come to nothing.

‘Where did you get to? You shouldn’t disappear without a word, I’ve told you loads of times …’

Sal spoke as if she were the parent issuing a reprimand. Nessa kept her lips tightly closed. Her daughter was barring her way at the door until she had her say. Darina sat at the table inside, clasping a teacup.

‘A policeman phoned from Bantry,’ said Sal. ‘His name is Redmond something, and he’s at the hospital now. He and his inspector want to come over to see you tomorrow. They’re anxious to clarify the details of the incident, as he put it, and to enquire into all the circumstances of the case. You know the way gardai talk.’

‘OK, love, I’m sorry I missed his call. But did he mention how Maureen is now?’ Nessa smiled, remembering Sal’s earlier needling. ‘I presume you didn’t forget to ask about her?’

‘You presume …? Ha, ha, don’t be smart, of course I asked about her. He said Maureen is as comfortable as can be expected. Whatever that might actually mean.’

‘It’s always the same bland line, isn’t it?’ said Darina, who was still pale, but seemed less strained than earlier. ‘I hate the way hospitals tell you nothing on the phone.’

Nessa decided that she would look in on her son Ronan, who had gone to bed late, and then get back to the garda in Bantry. But as she noted the garda’s number, she remembered her daughter’s homework. Sal had just started her final Leaving Certificate year at school, and had promised to stick to a strict programme of study. But unsurprisingly, she had not opened a schoolbook all evening.

‘Could I give you a lift home in about ten minutes, Darina?’ Nessa glanced out at the garden. ‘I think it’s about to rain.’

Sal gave their young neighbour a meaningful look. ‘Well, are you still on for Kenmare, Darina? I wouldn’t mind joining you, and I’m sure you’d like company tonight—’

‘Hold your horses now, Sal,’ said Nessa. ‘If you think you’re going anywhere on a weekday night, you can forget it. I’m sorry, Darina, I hadn’t realised that we’d upset your plans for the evening.’

‘It doesn’t matter now,’ said Darina. ‘I’d just mentioned earlier that I might go to a music session in a pub in Kenmare. But really, I don’t feel like it.’

‘OK then, but tomorrow night is definitely on, Darina, isn’t it?’ Sal looked defiantly at her mother. ‘Friday night, see? We’re both invited to a big party and you can’t possibly, like, lock me up for the weekend, can you now?’

A knock on the kitchen door prevented Nessa’s reply. It was opened cautiously and Fergus Malden stood looking at them. Unlike his father, he was shy and rather quiet.

‘Excuse me,’ he said uncertainly. ‘If things are too busy … But my stomach is still upset and I thought, maybe …?’

‘Come in,’ said Nessa. ‘I’m sorry you’re not feeling any better.’ Earlier in the day, she had accompanied him to the nearest town, Castletownbere, to go to a chemist. It was one of the reasons her day had been so busy.

‘I can wait until the kitchen is quiet.’ He seemed about to close the door again. ‘I was going to heat up some milk but if I’m in your way …’

‘It’s no problem, Fergus, please come in and I’ll do it for you.’ Nessa opened the fridge. ‘You know you’re welcome to whatever you’d like.’

‘I wonder if I could ask you …?’ Darina removed her jacket from the back of her chair and spoke quickly. ‘I’m Darina O’Sullivan, we met over at my studio on Tuesday and I spoke to your father again this morning, down in the village. He told me he might call in to the Barn before he left Beara, but as he didn’t make it …’ She bit her lip as she continued, ‘I hope you won’t mind my asking, because I’d hate to be pushy—’

‘You’ll have to up your sales pitch, Darina,’ said Sal with a laugh. ‘What you’re really trying to say is that you’d love Fergus’s dad to commission a painting or a portrait from you. The great Oscar Malden as rendered by Darina O’Sullivan, isn’t that your idea? But now you’re afraid you’ve missed your chance?’

‘Of course, whatever I can …’ As Fergus spoke, Nessa noticed how grey he looked. For her own sake as well as his, she hoped fervently that he would recover by Saturday. She could hardly wait to put her feet up.

‘Well, that’s it, I actually did a drawing for him today, just a little thing on a card, but I’d like to put a few finishing touches to it.’ Darina hesitated at the sink, cup in hand. ‘I didn’t have time this evening, but tomorrow …’

‘That’s OK. I’ll give it to him and I’m sure …’

Fergus had a habit of tailing off his sentences, and Sal joined in again. ‘You could bring it over in the evening,’ she said to Darina, ‘when you come to collect me for the party.’ She winked conspiratorially at their neighbour, and in spite of her worries about homework, Nessa was glad to see them becoming friends. There were very few young people in the immediate area, and as a result, Sal often pestered her parents to be allowed to gad about further afield. As for Darina, Nessa suspected that her life was rather solitary – she had lived alone since her mother, barely into her forties, had died of cancer a few years earlier.

Nessa poured warmed milk into a cup. She felt exhausted, and did not argue when Darina turned down a second offer of a lift home. As their neighbour was leaving, Sal gave her a big hug.

‘Thanks so truly much,’ she said with a giggle. Their plans for the following night were clearly well-advanced. ‘Or what do they say in Spanish? Muchas gracias, mi amiga!’

Fergus retreated and Nessa went upstairs to her son’s bedroom. At twelve years old, Ronan had a very active imagination and had plied her earlier with questions about Maureen and the ambulance. Now he was asleep with a book on his chest, so she turned out his light and tried to phone the garda in Bantry, a large town over forty miles away. She had forgotten whether his first name or surname was Redmond, and when his answerphone came on, Nessa just left a message to say that she could meet himself and his inspector at Cnoc Meala the following afternoon.

Sal was busily working her phone in the kitchen. ‘The others have gone down to Derryowen for a drink,’ she said. ‘The French couple, that is, and the two sisters – Zoe and whatshername, the quieter one. No doubt they’re discussing this evening’s excitement over their pints.’

‘Not the kind of excitement we advertise, unfortunately.’ Nessa poured wine for herself. She could arrange for her guests to get a lift back from O’Donovan’s pub in Derryowen, if they decided against the long walk up the hill.

‘By the way, have you heard the rumour?’ Sal paused in her fingerwork. ‘The latest on Maureen’s love life?’

Nessa took a slow sip of her drink. She was in no mood for new dramas, and just wanted to escape to her room with a comforting glass and a book. A good night’s sleep would renew her habitual curiosity about her fellow human beings.

‘She was seen upstairs last night,’ Sal continued. ‘Maureen, that is, while Dominic and a few others played cards in the living room. And the big rumour is – wait for it – that she got lucky in her love quest.’

‘You’d better spell it out for me, love. Is this about Maureen and Oscar, or is there another entanglement I haven’t heard about?’

‘It’s about Maureen going into Oscar’s bedroom. One of the two sisters – not Zoe but the other one, Stella, isn’t it? – went upstairs at about half ten, to look for a book she’d mislaid or somet

hing. Oscar’s room is opposite theirs and who does Stella see going in to him but Maureen? How about that now?’

‘Maureen might have been inviting him to join her husband’s card game,’ said Nessa drily.

Sal smirked in response. ‘Yeah, right. But the thing is, she wasn’t in a hurry about it, because according to Stella’s account, Maureen was still in Oscar’s room when Stella came downstairs at least, oh, ten or fifteen minutes later.’

THREE

Friday 18 September, 2.30 p.m.

The beguiling Beara peninsula, as the guidebooks had it. Craggy purple mountains and soft green farmland, not to mention the usual touristy stuff about boats bobbing on the waves. And, of course, hospitable people who loved to welcome strangers.

Redmond Joyce was not enticed by the image, no matter what others told him. All he could see of Beara was a low sky and persistent grey drizzle on his windscreen. He was on his way from Bantry, outside the peninsula, to Castletownbere, its main town, and from there to Derryowen. He was always amazed that people chose to spend their holidays in such places – bare and lumpy mountains, roads twisting across an empty landscape, nothing in sight but bleak loneliness.

It looked better in sunshine, of course. But even so, it would not attract him. To him, one mountain was the same as the next, and staring at a jumble of stones and water was not his idea of a good time. As for the people, he would run a mile from their kind and hospitable attempts to make conversation. What he wanted on holidays was to escape to one of the world’s great cities – Berlin, Singapore, New York, Rio de Janeiro – where he could feel the ceaseless throb of activity on all sides. Noisy crowds, a clamourous din and, best of all, not a soul who knew him.

Deadly Intent

Deadly Intent